Benjamin Murphy’s Lavish Entropy Catalogue essay by Andrew Salgado

Tonight is our private view at 67 York Street, Marylebone! Lavish Entropy is a solo exhibition by Benjamin Murphy, an internationally exhibited artist who is most well-known for creating darkly alluring monochromatic, figurative, line-drawings using the esoteric medium of electrical tape.

We are delighted to publish here our catalogue essay written by Andrew Salgado:

Benjamin Murphy is a Romantic – he strolls in wearing all black, of slight stature, looking appropriately broody with skeleton rings on each finger that he’s made himself and decked out in stylized tattoos – most of which he’s designed (and also probably executed upon) himself. He’s the embodiment of his own work; where art- meets-life-meets-art; probably a Kafka novel somewhere in his bag and a journal full of sketches and notes. He’s a bit like I imagine the old Romantic poets, literal manifestations of the very subjects of their poetry – the artist, in beautiful torment, unable to function properly as the very obsess to create somehow overwhelms them. A quick Google search reveals the tenets of Romanticism – the tenets I have long forgotten from my own time in art school – and they reveal themselves like a checklist of Murphy’s work: belief in the individual; reverence of nature; interest in the supernatural or gothic; interest in the past; nostalgic world-view. All of these, I would argue, form the foundations of Murphy’s work.

Over the course of the past few years, Murphy’s artistic practice (well, truthfully it has become something of an oeuvre, hasn’t it?) has grown to encompass his trademark ‘black-electrical-tape’ drawings; traditional pen-and-ink drawing; stitching (by hand, laborious and pain-staking); painting; prose; poetry; and even playwriting. I’m sure he also must play a musical instrument or two, and probably has a number of other tricks up his sleeve, like the ‘ five finger knife game’ (aka stabscotch) and must be brewing a bathtub full of gin somewhere. But the point is, this is a multifaceted talent who choses to focus his art on an aesthetic and ethos that is so well-rounded and thought-out that many artists working a lifetime would be jealous of. While his work has grown in terms of technique – which was already rather exceptional a few years back – what one sees now is an artist fully realizing his creative potential. There is never a summit for him, and I often talk to Murphy (well, Ben, to me when we aren’t being professional) and while I’m watching Come Dine with Me after a day in studio, he’s already done 8 hours of tape-drawings and has since been underlining prose in Baudelaire or Camus. What this obsession with work has created is now visually represented in these impeccably and profoundly executed tape-drawings: it is most evident in the triple-tier glass works, where ghostly shadows from layers of intricately detailed surfaces bounce and react

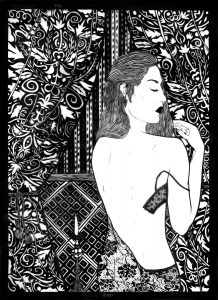

upon each other. One work, Ghost (2018), depicts an undressing female before a slew of Modernist paintings – and lace curtains draping before a patterned floor, another pattern here, the fronds of a Monstera plant in the back. If you consider the actual work and intensity of mark-making, it’s astounding. When we remind ourselves that this work is executed in tape, not pen-and-ink, it is simply a gobsmacking display of talent. But again, I reiterate the idea that this sort of exhibition comes after years of practice – of obsessive focus on one thing, and the elaboration of a technique he has basically trademarked as his own.

Like many works in the exhibition, the aforementioned piece is characteristic of a Murphy work but also characteristic of the tenets of Romanticism: firstly, imagine Murphy at work, and thus we have the solitary pursuit of an artist, working to depict the solitary moment of a character, usually in a decadently overgrown Victorian setting, usually depicted as a memento-mori or vanitas, viewed upon in her private moments with a type of gentle reverie. There’s a subtle nod to Degas, with the undressing solitary beauties; but also Matisse, when he’s looking at interiors or plants or even patterns; and even a slight nod to punk-rock, Shakespeare, or even Tarantino: knifes, feathers, needles, that sort of thing. But what I love about Murphy’s work is its inherent sweetness; given its unflinching

monochromatism and his love of Nihilist literature, I think the easy route would be to slip into cynicism. But there’s such an adoration of his own craft and the sensuous care of his own materiality that the work carries with it an inherent delicacy, a kind of grace wound into its very make-up, like a type of macabre but beautiful poetry in itself.

I look forward to the day we can sit in a theatre, watching Murphy’s debut play upon stage, with the set-design that he’s created, all scored to music he wrote. It will be an atmospheric, theatrically sombre event, dimly lit, set to candlelight. A bit of a Cabinet of Doctor Caligari vibe, I’m sure. So while the lights are on, spend some time with these works, consider the patience and care it would take to execute even just a small one. With those thin carefully delineated lines marking each individual strand of hair, or the articulated stigma of a flower, or the undulations of lace. Just as the Romantic and himself lost in their own rapturous creation, these are marks that describe countless hours of obsession, and as this young career continues to evolve, one can only imagine how its varying facets will continue to intermingle into a further fully-realised beast.

By Andrew Salgado, 2018