Collective Ending, A Land of Incomparable Beauty

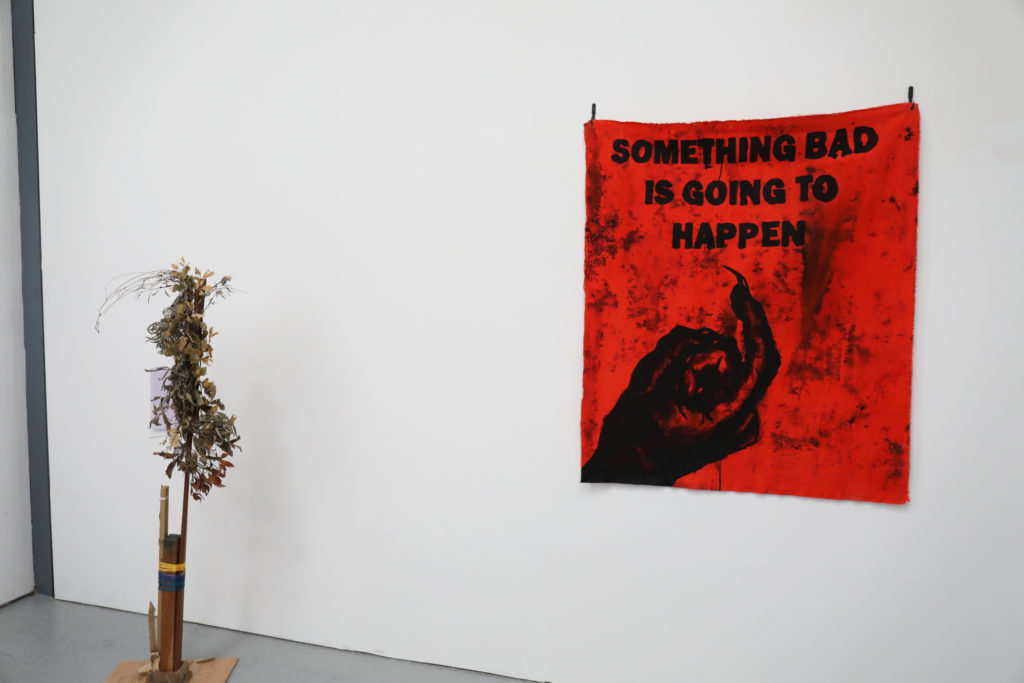

A flag hangs on a wall with a creeping, knobbled finger curling in invitation. Above the finger is written in large black letters, ‘Something Bad Is Going To Happen’. I wonder, had I seen Allen Gardener’s gnarled hand and ominous message in March, would I have taken it so presciently? It is trite, and most certainly over-done, to compare everything along a pre- and post-pandemic line, but in this show where everything speaks of the spectral, the weird and the mantic, I can’t help but see it as prophecy.

As Gardener’s work predicted, something bad did happen. Stalled by the global spread of coronavirus, Collective Ending‘s first show in their new HQ was delayed until the beginning of July. After staging three bacchanalian shows in the Spit & Sawdust pub in Bermondsey, titled in the series ABSINTHE, the group has settled in its HQ in Deptford, a large double-height warehouse with studios nestled in the eves and at the rear. Having a permanent space, and one in which its members can work alongside one another, is fuel for the group’s mission: giving art back to the artists, empowering them through reciprocal relationships. Collaboration, working against the scarcity ethics of the art world, is a central value of the group, hence its invitation to thirteen artists outside of the collective to display their work in its new space.

And they have followed the theme of the weird and the uncanny that began with ABSINTHE. A Land of Incomparable Beauty tells of “the sinister and eldritch underbelly, the skull beneath the skin of the countryside”, as the curators describe. It pries apart our construction of rural utopia that is particular to England, looks in its corners and behind its twitching curtains. The proximity between nature and horror is keenly felt; upon arrival, you are greeted by a spidery, twisted canvas by Luisa Mè, its arms reaching and crawling in terrible technicolour. There is an eeriness, a sense of threat from the phallic, totemic, sculpture of Irvin Pascal, and the Celtic symbolism of Jonathan Kelly’s twin canvases studded with rudraksha seeds.

The philosopher Mark Rowlands has written that “when life is at its most visceral, and therefore also at its most vibrant, it is not possible to separate exultation from terror.” Like this, all the impeccable utopia that we imagine exists in the countryside is underwritten by a second script, a buzzing, uncanny monologue. A Land of Incomparable Beauty alerts us that our view is partial. I grew up in Somerset, a beloved corner of England’s countryside, the ‘hush of nature’ where Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Jane Austen wrote. And yet I saw more of my home turf in this exhibition, with all its darkness and mire and collapse, than in any pastoral landscape.

Yet this show is not simply about stripping away our constructions, but about filling in gaps. It illustrates the longing in the utopic vision of England’s “green and pleasant land”. Our nostalgia for the rural denotes much more than a loss of the natural, but a sense of the loss of the human, of man’s connection to the authentic and divine. Works like Beth Emily Richards’ audio piece, a recording of Cornish residents performing a lost choral practice formerly used to send messages to heavenly friends or loved ones, and Hadas Auerbach’s glass plates, elfin drawings covered in baby’s breath and weeds, are reminders of the magic and mystery still alive underneath the housing estates and care homes, the out-of-town supermarkets and car showrooms.

The works on display are powerful, considered. It takes an adjustment of the eye to connect them to the curatorial theme, but it’s no bad thing for an exhibition to require some interpretative work. Besides, just as the underlying horrors of the countryside, the muck and the sublime, are beneath the surface, so is the impetus of this show; a humming, thrumming line connecting a diversity of artists through a compelling, unexpected theme. Marshall Berman’s description of modernity is one that fits well, that ‘to be modern is to experience personal and social life as a maelstrom, to find one’s world and oneself in perpetual disintegration and renewal… to be part of a universe in which all that is solid melts into air’. Like this, A Land of Incomparable Beauty reminds us that our eyes are gently blinkered, that the ground is not steady beneath our feet, that nature, spirits, the mystical lie always in wait.

Words by Stella Botes