Remi Rough in conversation with Dr. Charley Peters

Remi Rough (b. 1971, London, UK) began making paintings on walls and trains in South London in the 1980s. A respected train writer, Remi has maintained a dynamic presence on the street while developing a prolific profile as a studio painter, recently showing at MOCA (London), Wunderkammen Gallery (Rome), Zimmerling & Jungfleisch (Saarbrucken) and ArtScience Museum (Singapore).

I spoke to the artist about the formal concerns of his work, his relationship with definitions of his practice, and the legacy of abstraction in the ongoing evolution of his paintings.

Installation at Quarry Bay Station, Hong Kong for MTRHK and Swire Properties.

Hong Kong 2018.

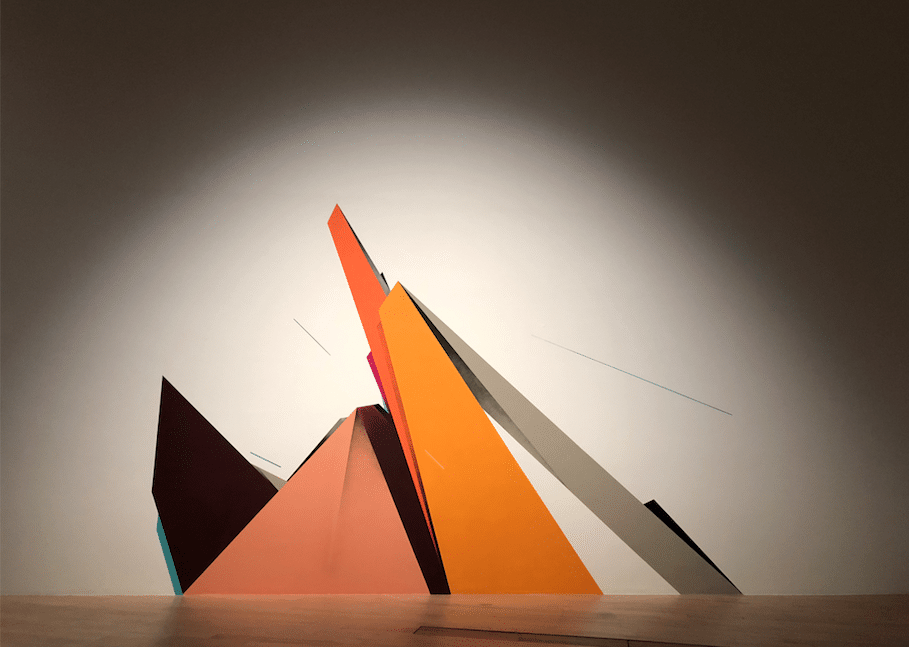

The Absolute _ 2017

Graphite, acrylic and spray paint on herringbone linen

120 x 120cm

Concise

Part of the ‘Art from the streets’ exhibition at the Art Science Museum, Singapore

Singapore 2018.