Dirtier Over Time – a conversation between Paul Weiner and Benjamin Murphy

Benjamin Murphy – First question: why are you an artist?

Paul Weiner – I don’t see much of a barrier between art and life. My work is the filter through which I understand what’s going on around me. I’m sorting through what I see in the world and tying the abstract to the concrete, so the works can be dramatic and painterly while also loaded with information and symbols that I’m recording from the world and spitting back out in my work. I end up with shows that are amalgamations of abstraction with the political and personal seeping in. At some point, the work takes on a life of its own through interpretations I setup or accidentally illicit. I live for those moments.

BM – Is that because you’re an artist, or do you not see a distinction between art and life in general?

PW – I do see a distinction, but I see art as a way of processing what we see in our lives. We each have mechanisms we use for making sense of the incredibly complex surroundings we inhabit. What’s so exciting about making art as opposed to, for instance, taking a long walk, is that the result can be a physical object and a relic of the time we live in for others to use later to make sense of their own lives.

BM – That’s a great way to look at it. Art is both a way for you to make sense of your life, but it can also perform the same function for others.

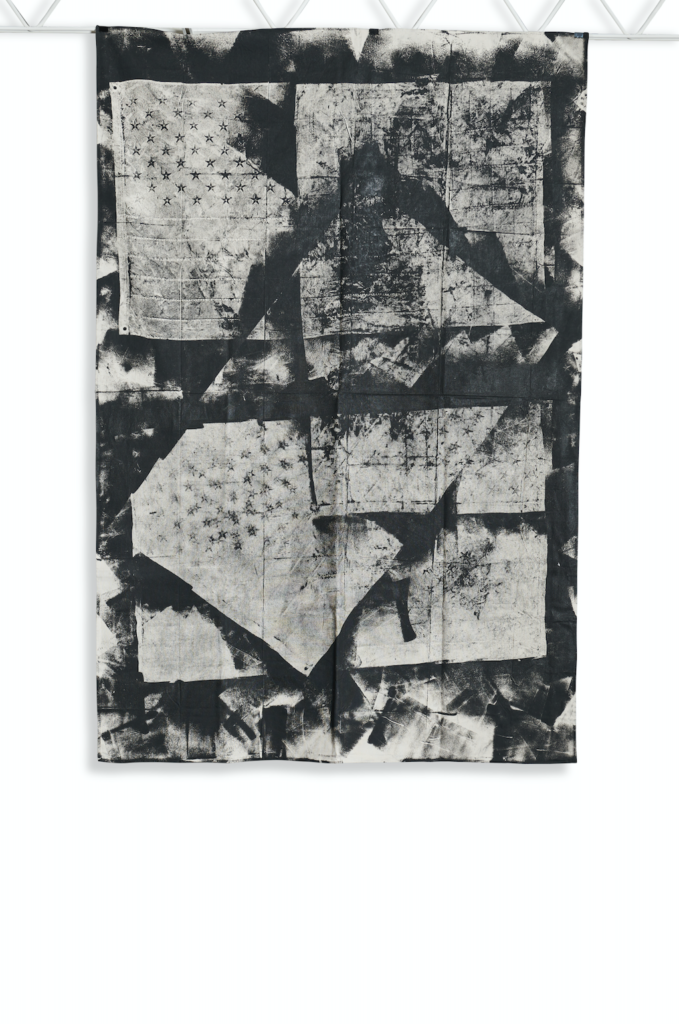

PW – Exactly. I want the viewer to see a broad range of objects from my most personal and emotional works to historical references and political information so they can find their own meaning and load the paintings with that meaning. There’s a level of abstraction in that most people don’t know exactly what my objects are when they first see them even though these are very politically and ideologically-loaded objects. Some of my favorite works hide in plain sight. You might be looking at shells collected from Tulelake internment camp, a mass shooter’s receipts, or toy guns soaking in a vat of Yemeni sidr honey without even realizing it. Those are subversive works almost hidden by their physical abstraction. Other works are more bombastic with pop art references that are more easily read – like my American flag paintings, so there is an energy in those works that informs the others. It’s hard to miss a 20 foot tall flagpole covered in advertisements for military weapons manufacturers hanging from the ceiling.

BM – So you you think artists have a responsibility to take a stand politically?

PW – No. Each artist is different, and we should all have the freedom to make whatever the hell we want to make. My works can be violent, beautiful, sexy, destructive, and ideological all at once. It’s a chaotic and maximal practice where I fit everything in under a big umbrella. Only a small sliver of my work ends up in the gallery and even less is on social media. I have a lot of surprises up my sleeve that I’m waiting for the right time to put out.

BM – Do you ever destroy works?

PW – It’s usually an accident, but shit falls all over the place in the studio and I break things on the floor all the time. It’s messy and charcoal or graphite gets on everything. The fire department complained about my studio last month, so I’m cleaning it up. Sometimes I still use works that I’ve destroyed. There’s something I like about evidence of my studio’s cannibalistic energy in the work.

BM – Hahaha yeah all that charcoal and oil your studio must be a fire hazard

PW – Yeah. I’m trying to clean up my act in 2020!

BM – Why do you do when a piece isn’t working, do you ever abandon them?

PW – Yes. The poured charcoal pieces are especially fickle. Sometimes I abandon them if I don’t immediately respond to the composition, but they age nicely as they get dirtier over time. Occasionally I overwork a piece and do just throw it away.

BM – Yeah that’s something interesting that I’d like you to elucidate, tell me about how your works alter over time, and why you choose not to fix them once you’ve finished painting?

PW – Some of the works do get fixed, but I like the idea of a drawing as less of a stable object and more of an image that evolves over its lifecycle. The unfixed works seem less commercial and less decorative in that way, which lends some authenticity to abstraction.

BM – Some of your works are quite expressive and almost chaotic, your charcoal works especially, do they come from that kind of place?

PW – They do. I also think of those works as being violent. I tend to use them to create drama within an exhibition, as is the case with my recent show at Nancy Littlejohn Fine Art in Houston. They soak up all the information from surrounding sculptures and become filled with those ideas even as they remain expressive. I’ve also thought of those works as a sort of reference to post-war abstract expressionism and the specifically Jewish nature of that movement. You arguably have some of the greatest Jewish art and criticism ever in that movement between the Rothkos, Greenbergs, Krasners, Frankenthalers, Gustons, Newmans, Rosenbergs, and others of that movement. At a time when Jewishness is back in the news, this work seems very pertinent. As much as those charcoal works are my own expression, they are almost sculptural references to a time wrought with war and the realignment of power dynamics on the world stage, somewhat mirroring what we see again today.

BM – Ah nice, a lot of Anselm Kiefer’s work is about the secondary guilt he feels as a German about the Holocaust. It isn’t necessarily directly referenced in most of his work, but it provides a context that affects the reading of his oppressive, gestural pieces.

So what would you say is the purpose of art?

PW – Art can serve so many purposes from person to person that I’m hesitant to define the purpose aside from the idea that it should illicit thought or emotion in some way. I don’t even think I know what my art’s own purpose will be 5, 10, or 100 years from now. I hope it will still be relevant.

What you said about Kiefer is interesting. I have always admired his work, especially the way he infuses history into his paintings to build these contemporary artifacts that merge our time with what came before. Kiefer takes on such a variety of incredibly powerful and controversial topics at once and marries them together in grandly emotional constructions of paint and materials.

BM – The febrile political climate that we find ourselves in at the moment is serving to inspire a lot of great art.

PW – Yeah. This climate of international power realignment leaves us in a constant state of flux, and the art we see today is reflective of these times whether it’s consciously made that way or not. It’s conscious for me, as is clear in my exhibition at Nancy Littlejohn Fine Art, which includes a variety of objects that are critical of war profiteering particularly targeting Raytheon, Boeing, Northrop Grumman, and Halliburton. Even as trillions of dollars are siphoned away from domestic American interests, there is a great deal of money to be made on American wars. US Defense Secretary Mark Esper, a former lobbyist for Raytheon, is a walking conflict of interests.

We’ve just learned of the American drone strike that killed Iran’s Qasem Soleimani, a powerful Iranian General. This is an act of war. Today, we are at an impasse where we will learn if any true opposition party exists that could force our president to deescalate American conflicts nearing war with Iran and elsewhere throughout the world. As abrupt as this massive military escalation feels, it didn’t happen in a vacuum. Just a few weeks ago, Congress agreed to a bipartisan reauthorization of the National Defense Authorization Act that granted widespread executive authority to the president and rejected an amendment that would have forced the president to seek congressional approval before this strike.

Crippling bipartisan sanctions on Iran were passed in a 98-2 US Senate vote in 2017, causing economic havoc that is particularly harsh for poor and vulnerable people. The sanctions have had the effect of limiting the import of medicines and causing cruel and needless trouble for sick people, especially pediatric cancer patients. In combination with a bipartisan $738 billion defense spending bill, the complicity of those who claim to resist Trump is palpable.

BM – Do you ever wonder what you would make your work about if you lived in a socialist utopia and had nothing to critique?

PW – I would be working hard to keep it that way, and my art would reflect that. I suppose important themes in my work would be solidarity, protection, and emancipation all still filtered through abstraction in some way. Any time a leftist reform is implemented, it’s vital to defend those reforms by creating a culture around them and organizing to quash the inevitable opposition from capital by limiting the resources available to that opposition.

I’m not fighting for a fantasy world or nitpicking about what constitutes perfect socialism, though. I’m just tired of a system that has presided over the unprecedented transfer of wealth to a few ultra-wealthy oligarchs at the same time as it filters trillions of tax dollars through endless wars that force unnecessary cruelty on people all over the world when that money could be used to improve domestic living conditions instead. I want a system where we don’t have to hopelessly watch as Australia and Jakarta burn while living in constant state of fear that there might be a school shooting down the street, we can’t pay our debts, or afford our medications and where we don’t have to hear about elites going galavanting around the world on Jeffrey Epstein’s pedophile airplane.

I want a system where people can go to the doctor when they’re sick without worrying about going bankrupt, go to a public college for free, put a roof over their heads, and earn a respectable wage to support their families without wondering if another pointless war will suck away all the resources tomorrow.