A Necessity of Sanity – Benjamin Murphy in conversation with James Tailor

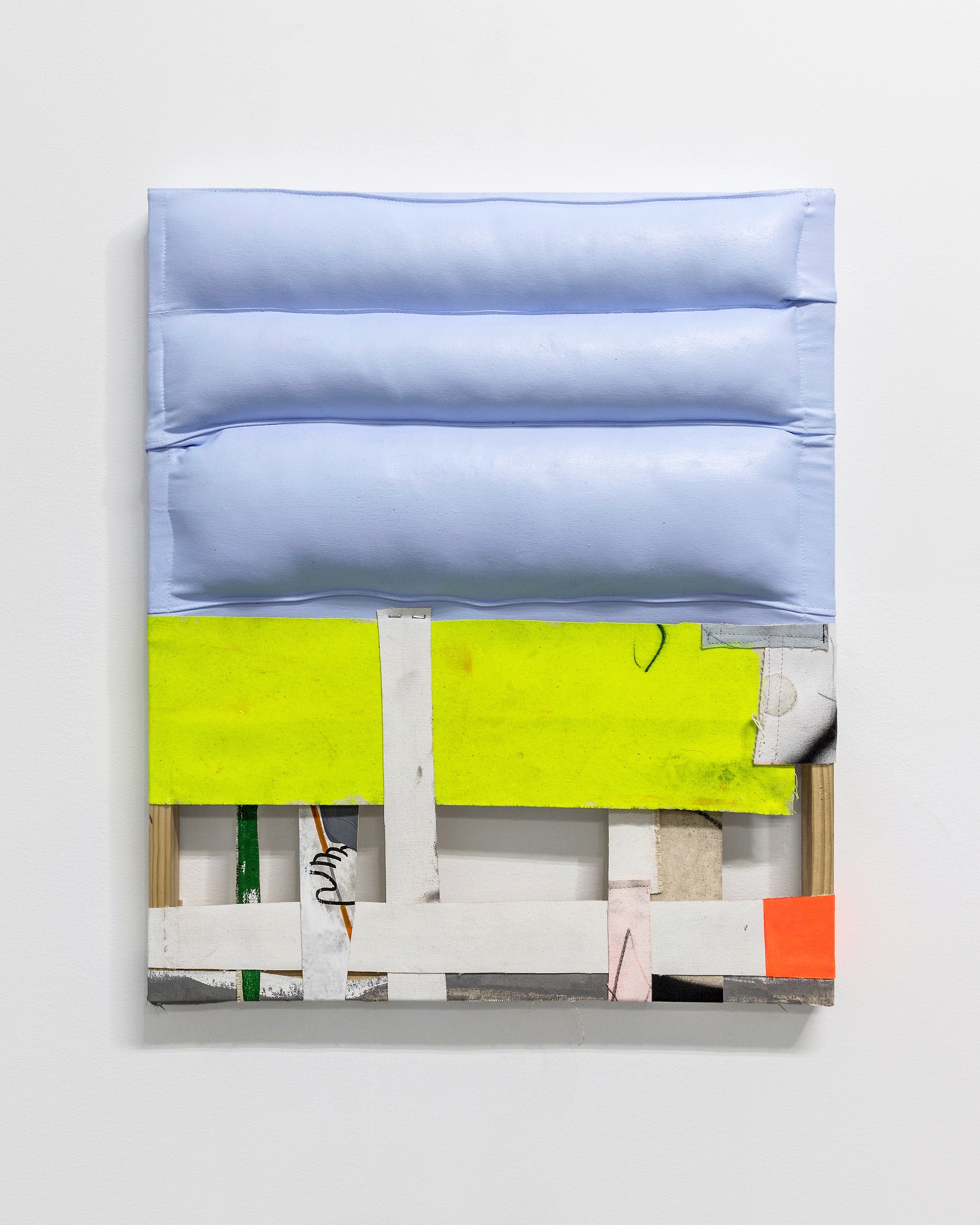

James Tailor’s work is deeply-rooted in theory, but is not bound to it. Rather, his abstract sculptures are to be approached on formalist grounds, open to interpretation. Whilst abstract, they hint at representation; visceral forms suggest the human object, both inside and out.

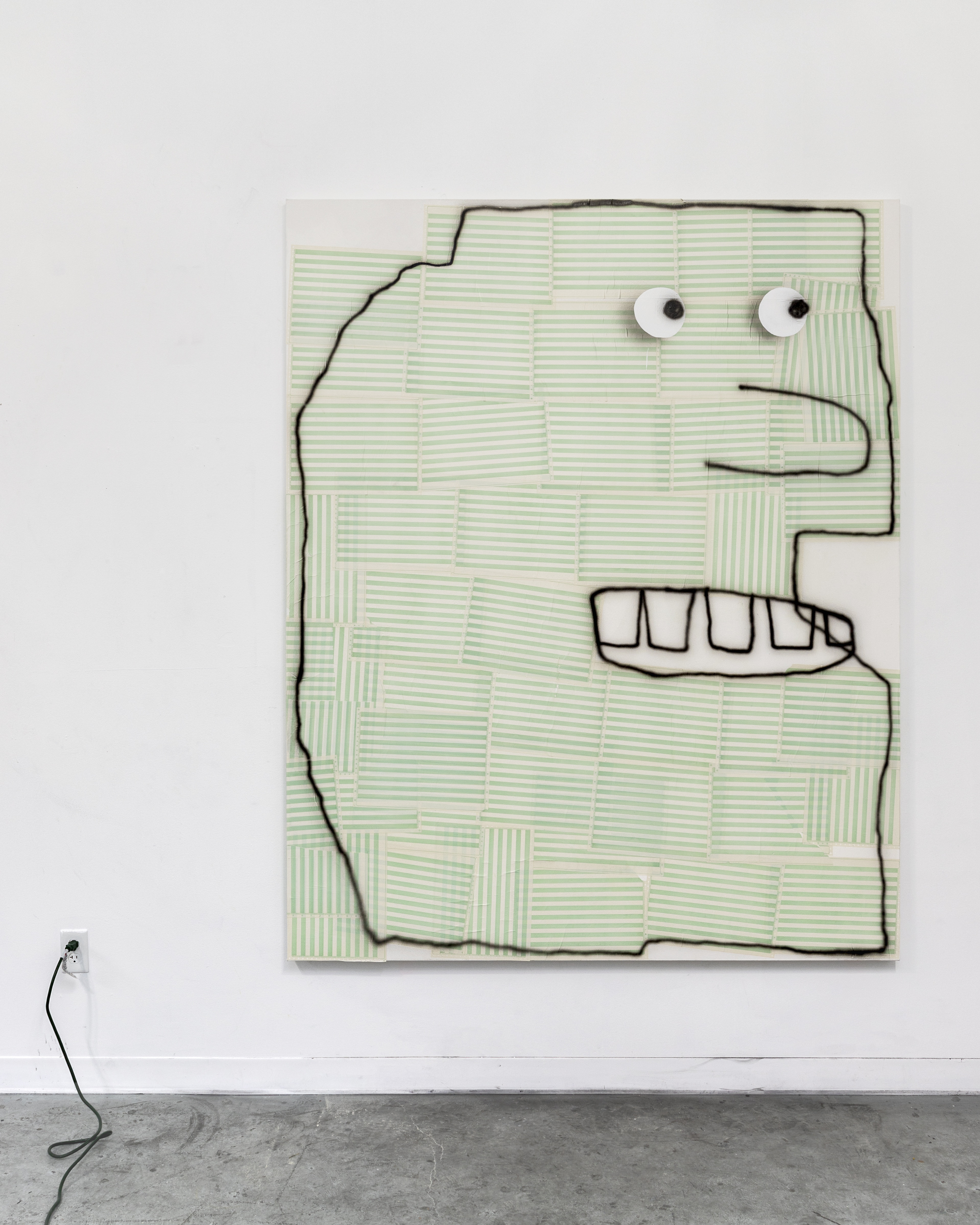

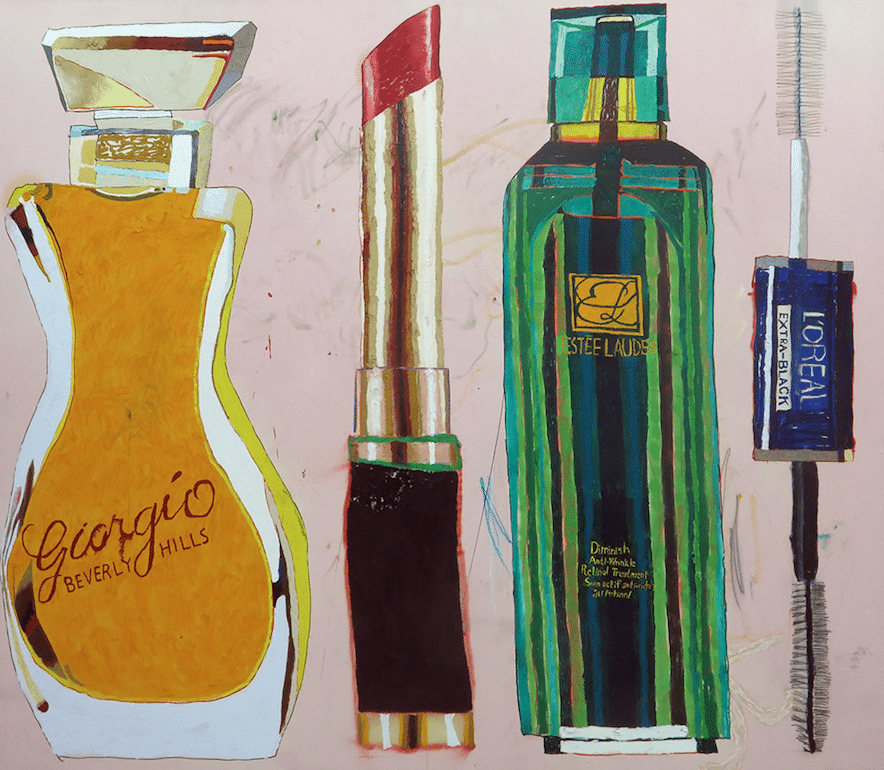

Medium: Acrylic paint on canvas and stretcher

Bulbous folds in the skin of some works speaks of human excess; gluttony almost, but never derogatorily.

His use of colour adds a layer of complexity, by alienating these forms and moving them towards the unknown, where any semblance of representation can only be the representation of something familiar, and yet somehow entirely new.

Why are you an artist?

The answer to ‘why I am an artist’ is rooted in my childhood, I struggled growing up with dyslexia and found Art to be the most successful way I had of communicating. Similarly, as an adult my constant reevaluating shows me that being an artist is my strongest hand, something that makes me truly happy and a necessity of sanity.

Do you think being an artist is intrinsically linked to who you are?

I don’t believe I’d ever find an alternative that I’m as passionate about, that if not engaged with after a few days, effects my sense of being. So for better or worse, it is intrinsic to who I am now.

What else are you passionate about

Making art is all-encompassing, leading towards many areas of research, personally I’m engrossed in exhibitions, art documentaries, podcasts, books, lectures, fashion, interior design and politics.

How does that research manifest itself in the works?

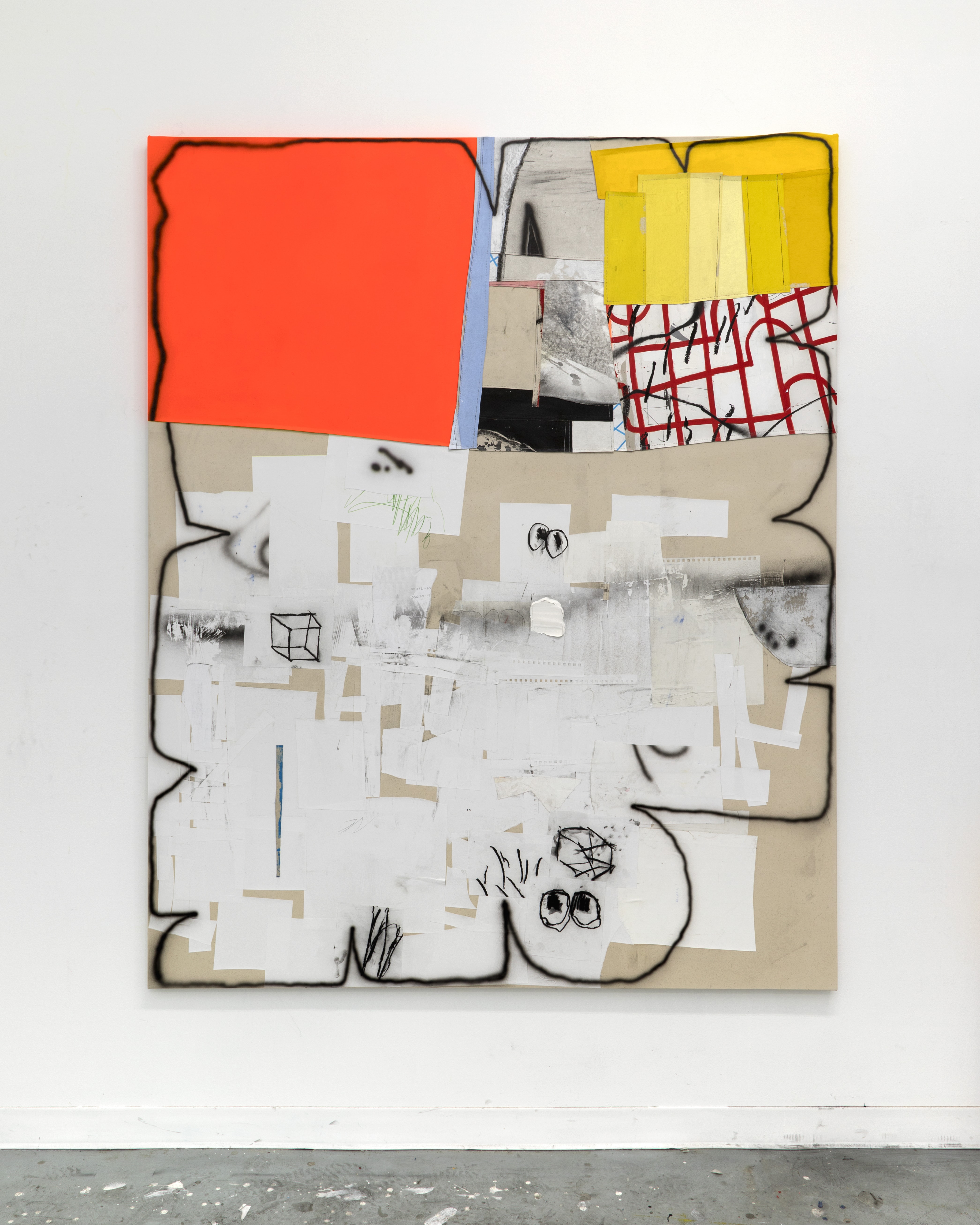

Medium: Acrylic & varnish paint skin pleated over canvas and stretcher

My research is the undercurrent, at the starting point and also in the contextualisation. Working in this way allows an ambiguity to be present that avoids directing the viewer too a said understanding of a given piece, this is achieved with subtleties like the size or tension in a break and the angles in between things, seemingly small choices or restraints can have very powerful connotations. People connect more with a piece if they reach their own conclusion but it’s my responsibility as the artist to make sure each piece is able to stand on its own as an intriguing object.

So do you want your work to be approached with formalist readings through which they can interpret the works in their own way?

It’s not important nor a requirement that the viewer understands all the different nuance’s in my work, there are different levels of engagement and this is considered. There used to be a point where I anchored my practice to painting, and although there is an undeniable link to that medium, this is no longer a primary concern of mine. Allowing my works to exist as they are, assemblages, somewhere in between painting and sculpture, allows space for new possibilities.

How do you approach the making of the works, do you have a specific feel in mind at the outset, or is that dictated by the medium?

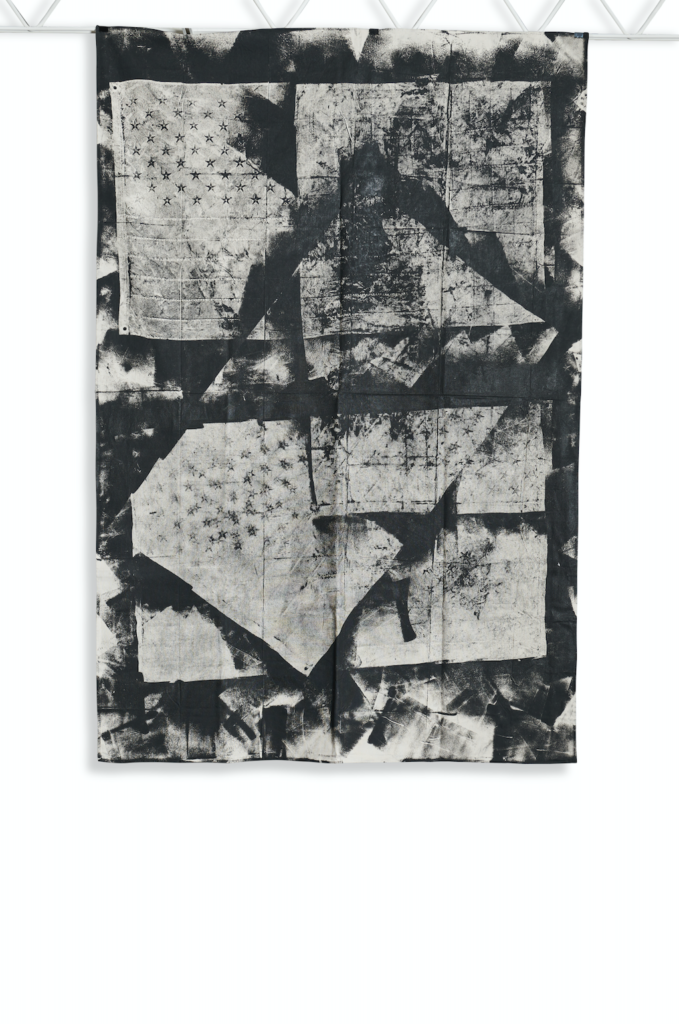

Mainly working with the possibilities chance and assemblage give, my practice is not tied to a particular medium or style. Taking found objects, usually at the end of their life and re-appropriating their narratives to form new ones, there is an unavoidably autobiographical meaning to be extracted from what I choose. I create assemblages from materials with which I personally connect.

The discarded items that I use convey an inherent sadness and a sense of anticipation, It is precisely that feeling what I cling to. These items are then sometimes paired with acrylic paint, which I obsessively rework into a self made material. There is something ridiculously excessive in my fixation with acrylic paint which can verge on addiction when reworking it again and again. Through draping, sculpting, casting or pleating I react to the tensions inherent to the materials and have to be able to judge when to stop.

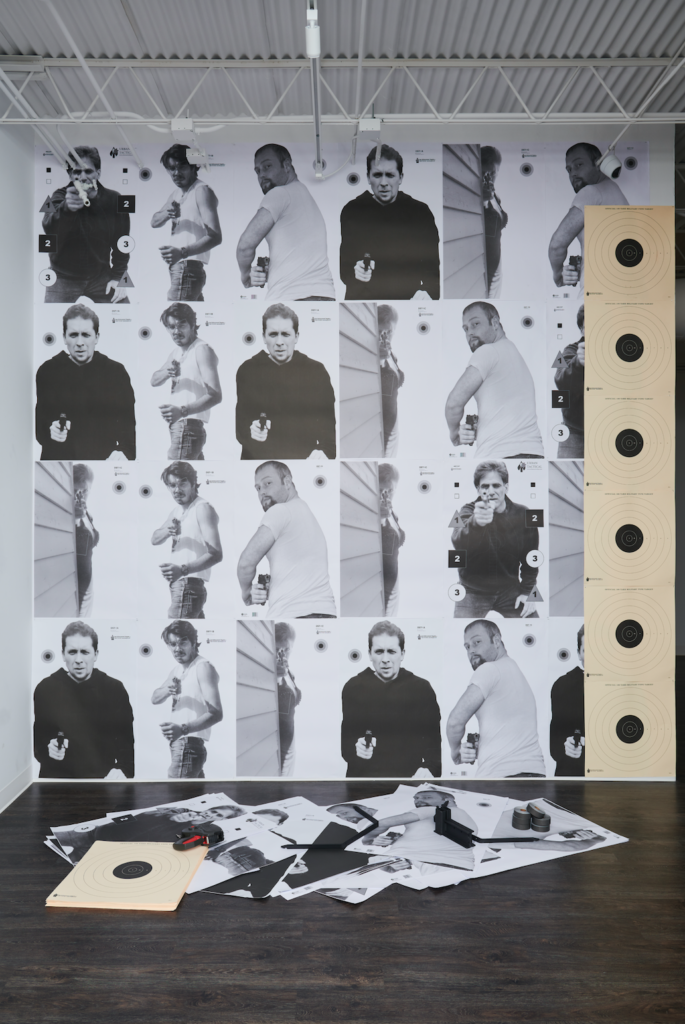

Medium: Acrylic paint skin pleated over canvas and stretcher with wooden crate including gloss paint and found objects

Where do you source these materials?

The objects used in my assemblages are broken discarded items that can be found anywhere. So it’s important for me to always be alert, never knowing when I may stumble upon the starting point of a potential new work.

The paint skins are made from paint medium and pigment, which are stocked in most art shops, structural items used are sourced from hardware stores.

Does the history of the medium ever inform the outcome of the work?

During my studies, and through out my career I have been fascinated by movements such as Dada, Art Povera, Suprematism and Conceptual Art but was compelled with the history of painting as a medium and the way it is viewed. My practice has been preoccupied with the phenomenological aspects of the materiality and reception of the art works and in particular with the way in which, in the present times of viral dematerialisation, I counter the melancholic severance of the discarded objects with which I assemble my sculptural pieces with the unifying quality of an obsessive reworking of those objects through (acrylic) paint.

Artist I have especially admired are Louise Bourgeois, Jannis Kounellis, Daniel Buren, Steven Parrino, Tony Cragg and Phyllida Barlow. Being aware of whats happened, or happening, undeniably informs me and its something I’m devoted to, its important to keep expanding on a knowledge that aids conversation, without repeating whats already been said.

BM – What is your work about?

TAW – I don’t ever intentionally make work about a specific subject, or try to direct viewers to see it in a certain way. Often I can overhear a segment of a conversation or something like that, and it sort of becomes a point of departure in a painting. I’m always interested in letting the work completely become unhinged from that initial prompt, and I never feel any obligation to circle back and force it to make sense, to resolve it

BM – So how does it make you feel when you look at it afterwards, and are there any signifiers within the work that you can identify as being related to certain things?

TAW – I generally don’t let a painting survive if it makes sense, I find it boring.

Sometimes symbols and shapes that I draw are interpreted as specific signifiers for something, but they’re most often based on my immediate interest in drawing them.

Sometimes that can result in something that maybe points to things happening in the subconscious l, but I’m comfortable with letting people interpret it however they’d like.

I also had a great teacher that once told me “you’re saying more than you might think”.

So I just kept going, firing from instinct and impulse.

BM – What is your work about?

TAW – I don’t ever intentionally make work about a specific subject, or try to direct viewers to see it in a certain way. Often I can overhear a segment of a conversation or something like that, and it sort of becomes a point of departure in a painting. I’m always interested in letting the work completely become unhinged from that initial prompt, and I never feel any obligation to circle back and force it to make sense, to resolve it

BM – So how does it make you feel when you look at it afterwards, and are there any signifiers within the work that you can identify as being related to certain things?

TAW – I generally don’t let a painting survive if it makes sense, I find it boring.

Sometimes symbols and shapes that I draw are interpreted as specific signifiers for something, but they’re most often based on my immediate interest in drawing them.

Sometimes that can result in something that maybe points to things happening in the subconscious l, but I’m comfortable with letting people interpret it however they’d like.

I also had a great teacher that once told me “you’re saying more than you might think”.

So I just kept going, firing from instinct and impulse.