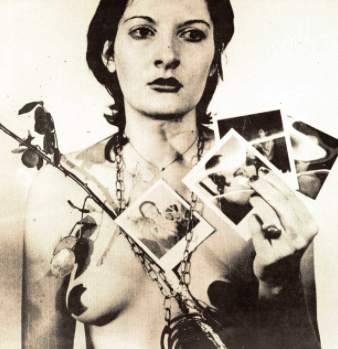

Marina Abramovic’s Rhythm 0

Marina Abramovic – Rhythm 0

Words and illustration by Benjamin Murphy – Originally published in AfterNyne Magazine

In 1974, twenty three year old Serbian-born artist Marina Abramovic created the most poignant and shocking performance artwork to date. Rhythm 0 was a captivating social experiment, and one that has still not been surpassed 43 years later.

Gallery visitors were met with a standing but immobile Abramovic, beside her a table containing a plethora of seventy-two seemingly unconnected objects. Some were clearly intended to give pleasure: a rose, grapes, perfume, and a feather were included. Some others were more sinister: a whip, nails, a razorblade, scissors, a pistol, and a single bullet.

The audience was then asked to explore the objects and use them upon her body in any way they wish, whilst for the next six hours all responsibility for their actions was assumed by Marina.

Placed upon the table was the following text.

Instructions.

There are 72 objects on the table that one can use on me as desired.

Performance.

I am the object.

During this period I take full responsibility.

Duration: 6 hours (8 pm – 2 am)

At first, the crowd was sheepish and their actions innocuous, giving her the rose to hold and generally not doing much. After a while, mob-mentality took control and the crowd got more vicious. With tears streaming down her cheeks Abramovic stood immobile and stoic whilst her clothes were cut off (in a similar way to Yoko Ono’s Cut Piecefrom ten years before) and her neck was sliced with a razorblade. The man who cut her then leant forwards and placed his lips to the fresh wound and drank her blood. It left a scar that she still has to this day. She was touched in intimate places, and according to art critic Thomas McEvilley “…she would not have resisted rape or murder”.

In the post-apocalyptic dystopia we see so often in books and films, once state authority is removed society becomes feral and vicious.

One visitor put the bullet in the pistol and placed it in her hand pointing at her own neck, no doubt willing her to pull the trigger. At this point even the gallery staff thought the work had gone too far, and “went crazy”, grabbing the gun and throwing it out of the window. All the time Abramovic never moved.

She was picked up and carried to a table, placed upon it, and had a kitchen knife thrust between her legs into the wood of the table, in a symbolic gesture that symbolizes both rape and murder.

Abramovic’s ability to transcend physical and psychological pain through sheer mental strength is astounding, but it is not the main focal point of this work.

What makes this work so frightening is that it took a simple absolution of guilt for this randomly collected cross section of society to resort to viciousness and disregard for human life. It calls to mind the Milgram experiment, in which volunteers were informed that they were required to electrocute another volunteer. The volunteers were unaware that the experimenter and the person being electrocuted were in cahoots, and any response to electrocution was staged. The confederate would be asked questions, and any incorrect answer was met with an electric shock – increasing in power for every subsequent shock.

In this experiment, the volunteer was absolved any responsibility, and therefore continued to obey the instructor, despite the obvious danger. Many of the participants showed visible signs of distress throughout, and were clearly complying begrudgingly.

It was an experiment to see if obedience to authority would overrule the volunteer’s conscience, and their natural fears for another’s safety. It questions whether the volunteers could be considered accomplices to the act, and was inspired by the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961, just three months before.

In Rhythm 0 however, not only did the viewers enact ‘real horror’, but they did so with relish. The audience was not acting under orders from an authority figure as they were in the Milgram Experiment, but were given the authority to act autonomously. In the Milgram experiment, most of the volunteers protested the instructions and showed many signs of extreme distress, but in Rhythm 0 they seemed to enjoy what they were doing.

One would expect that the participants would display reticence to act freely due to the Hawthorne Effect (the modification or dilution of ones natural behavior due to the knowledge that one is being observed), but this is actually not the case, as the participants showed an eagerness to experiment in ever increasing gradations of severity.

It is also possible that the absolution of responsibility allowed the spectators to play out some of their darkest fantasies. The symbolic hematophagy is suggestive of the participant assuming power or control over Abramovic, and asserting their dominance.

They saw Marina as an object, and they played with her sadistically like a cat with a mouse. They were also required to use their own creativity when deciding in which way the objects were used, and it is surprising how quickly they abandoned the safe objects in favor of the truly dangerous ones. The dehumanization that occurs is in part due to Abramovic’s immobility, in part due to her silence, and in part due to the acts of objectification enacted upon her by other members of the crowd. It is in part because the spectators saw their contemporaries enacting hostilities that they felt able to also.

She took some of the ideas originally explored just 13 years prior, and took them to their most extreme point.

Performance art is similar in many ways to theatre, but as Abramovic has shown there are some subtle but definite differences. Horror within the theatre is inauthentic, but at least in some cases, within performance art it is real.

In 1891 Oscar Wilde explored this topic in his essay The Critic As Artist.

“…Art does not hurt us. The tears that we shed at a play are a type of the exquisite sterile emotion that it is the function of art to awaken. We weep, but we are not wounded. We grieve, but our grief is not bitter.”

Almost a hundred years later, Abramovic proved this to be incorrect.

For more critique by Benjamin Murphy