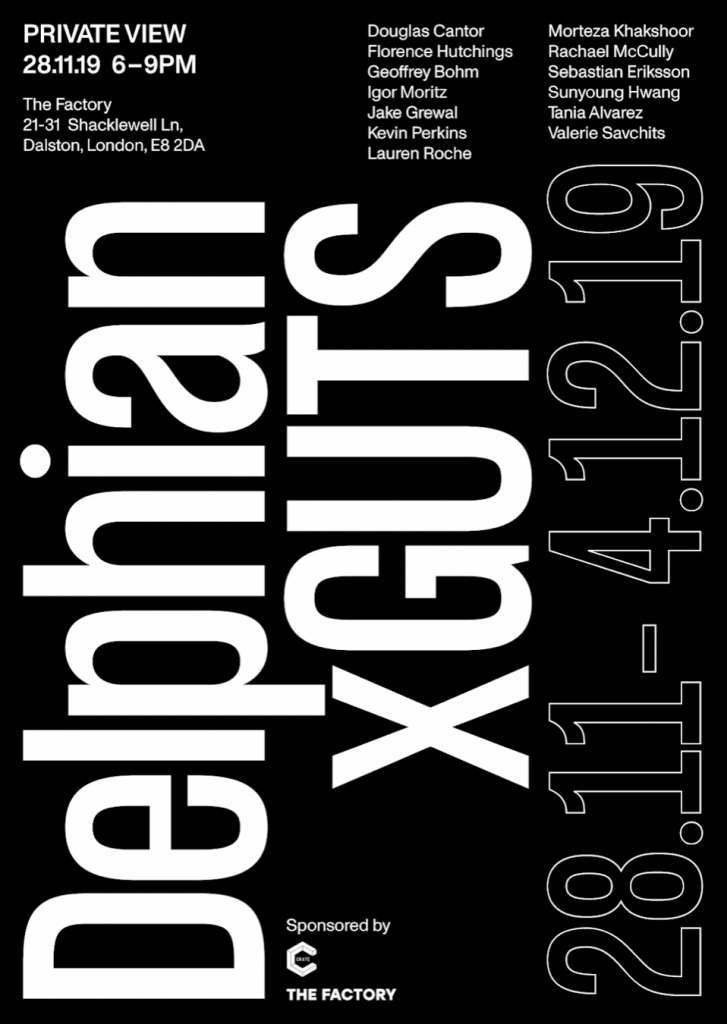

Delphian X Guts

Join us for the private view of the Delphian Gallery X Guts Gallery collaboration exhibition with the most exciting contemporary art around.

Private View Thursday 28th November 6-9pm

Exhibition continues until Wednesday 4th December

Socially, politically, and economically, we are living in trying times. These difficulties create division, and division breeds competition. We endeavour to support all art-world practitioners wherever possible, whether they reciprocate or otherwise, and to collaborate with what would (by some) be called our direct competitors. We believe that the art-world would be a much more open, supportive, and progressive place to work if we started working together, rather than pulling apart. For this reason, Delphian and Guts have decided to join forces.

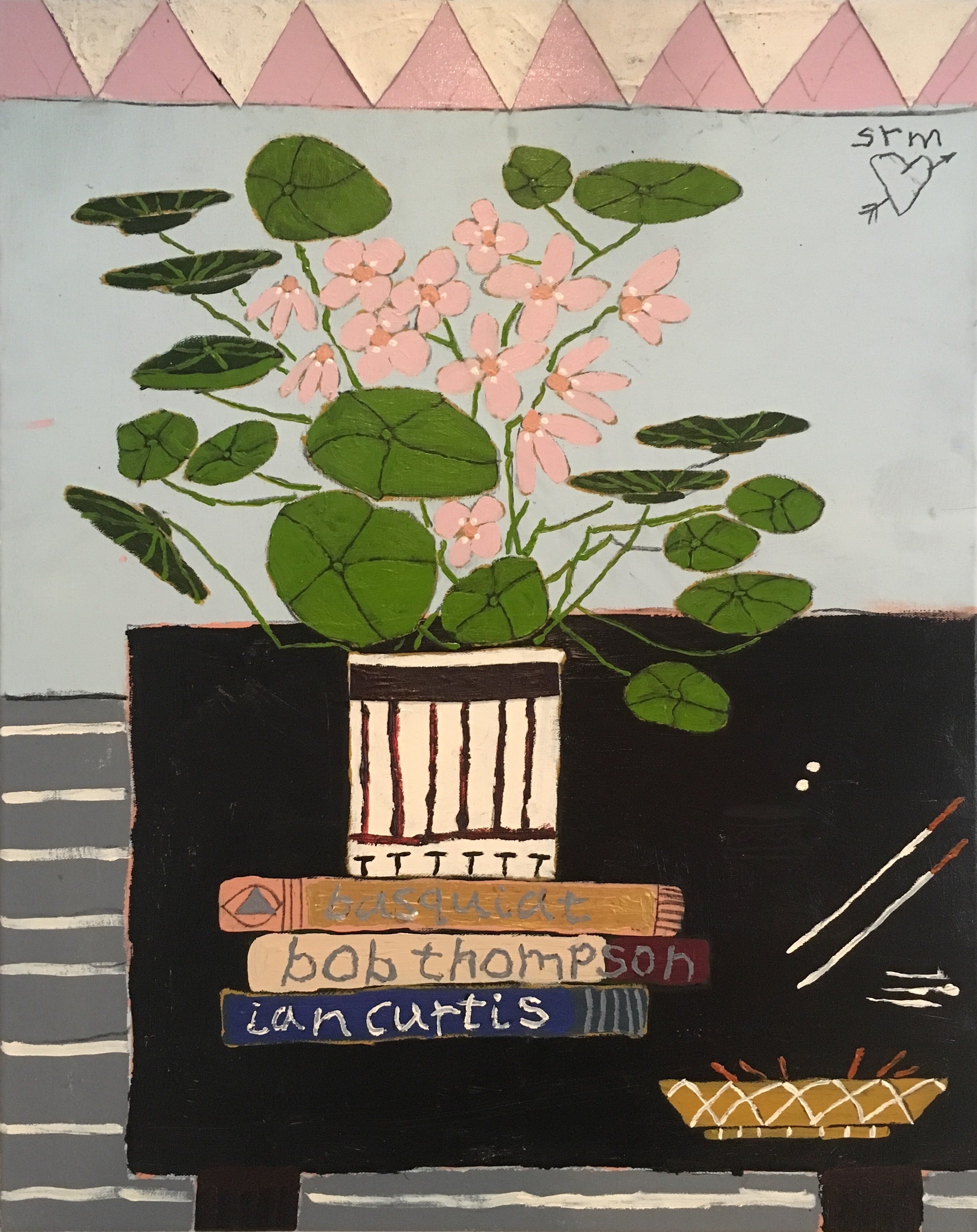

Exhibiting Artists

Douglas Cantor, Florence Hutchings, Geoffrey Bohm, Igor Moritz, Jake Grewal, Lauren Roche, Morteza Khakshoor, Rachael McCully, Sebastian Eriksson, Sunyoung Hwang, Tania Alvarez, Valerie Savchits.

Generously supported by The Factory and Crate Brewery

Opening Hours

Monday: 11am — 5pm

Tuesday — Friday: 11am — 7pm

Saturday: 8am — 7pm

Sunday: 10am — 6pm

*RSVP for the guest list here*

For the catalogue of available works, click HERE

For more about our past shows, click HERE