Who is it real for? The internet as vehicle

Who is it real for? The internet as vehicle by Kate Mothes

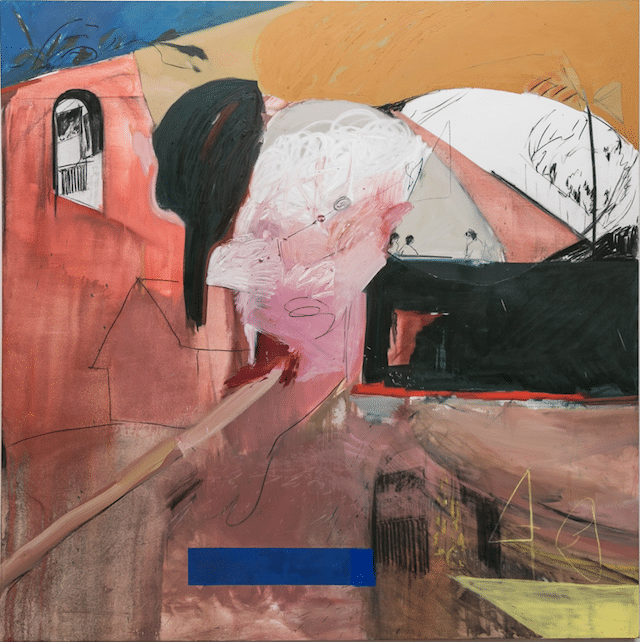

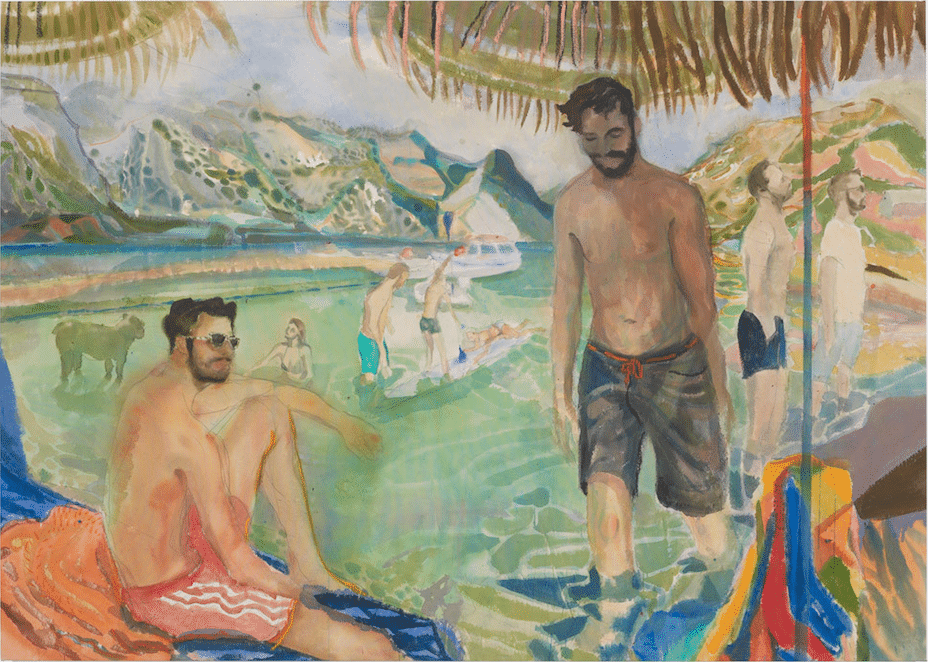

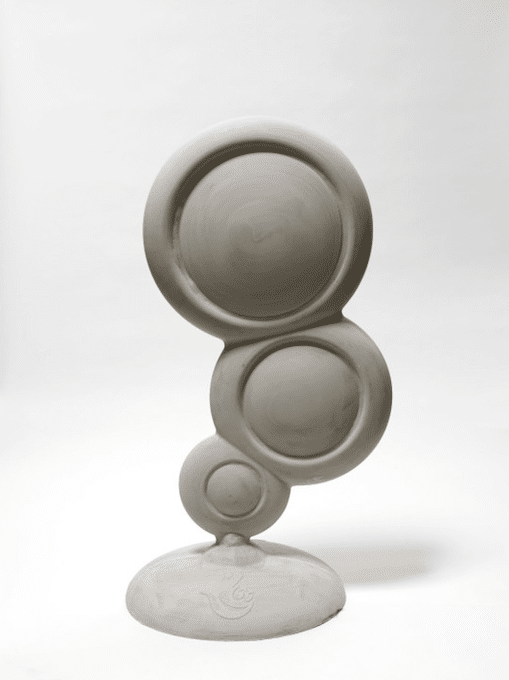

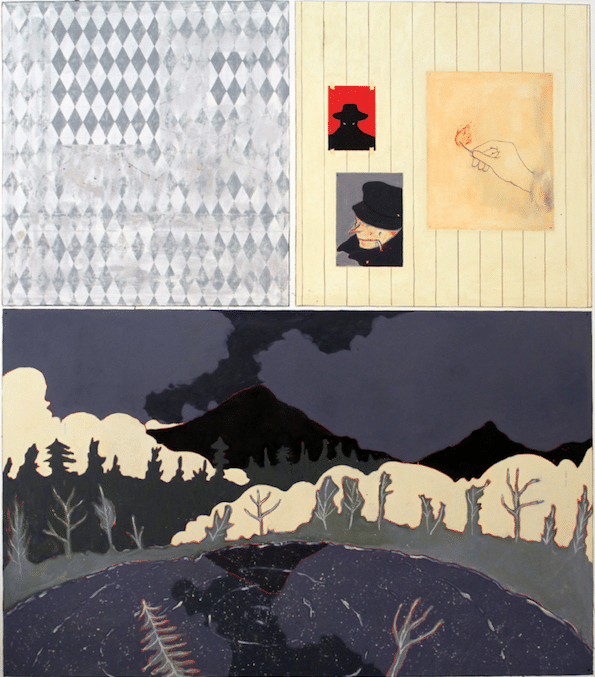

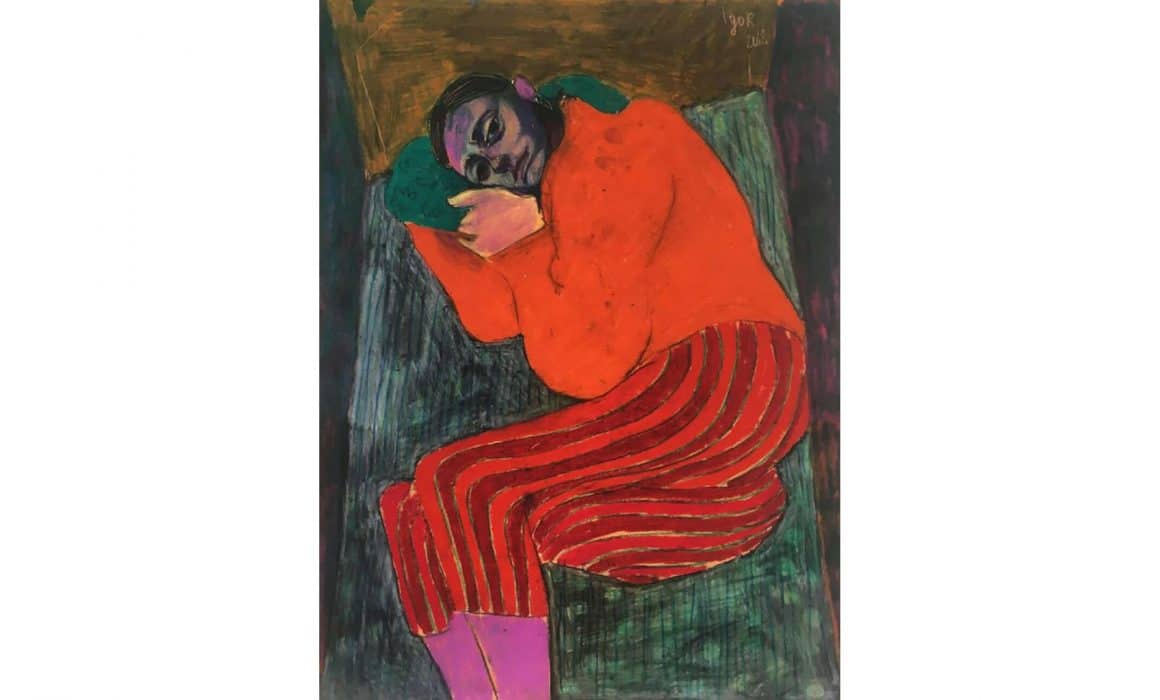

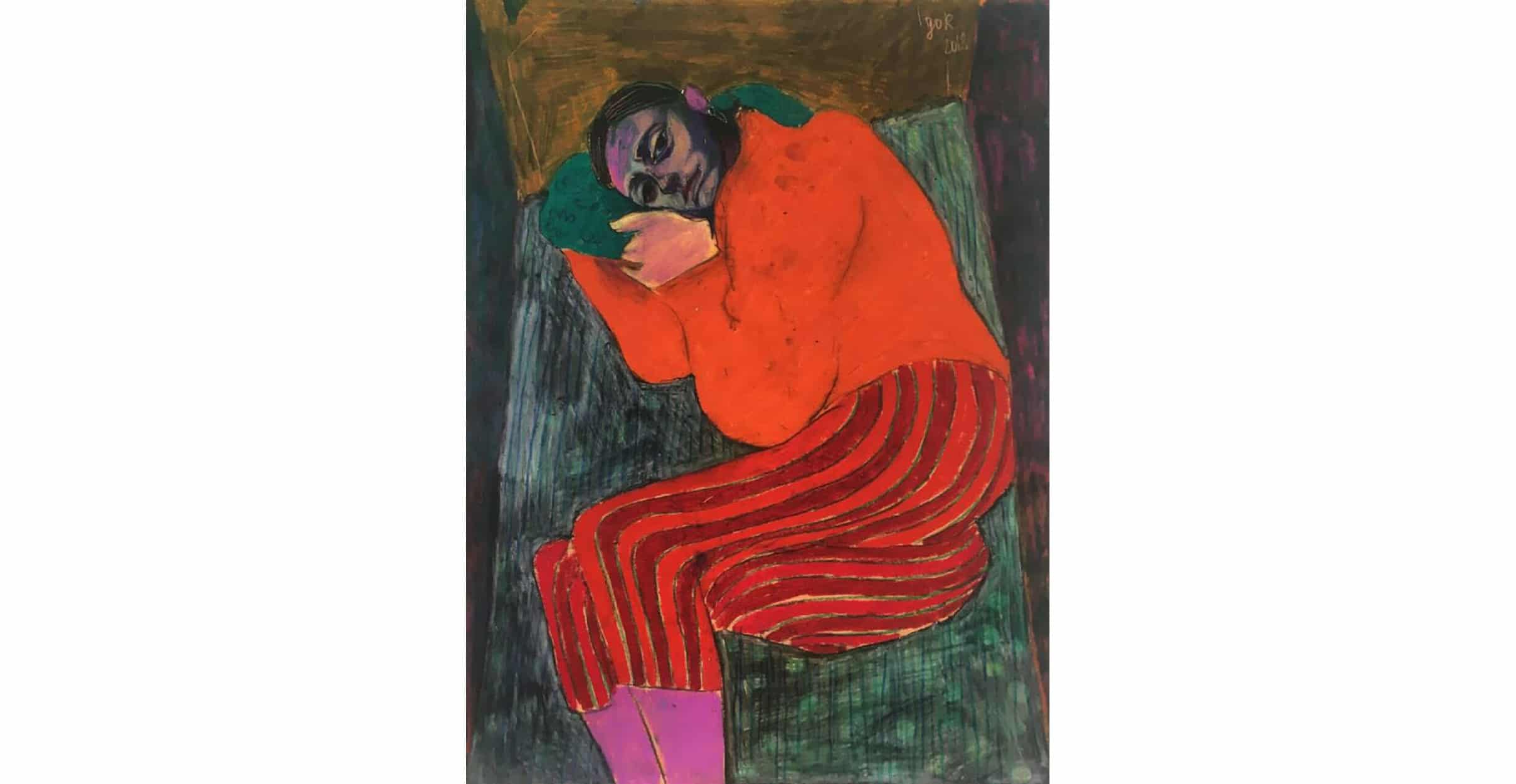

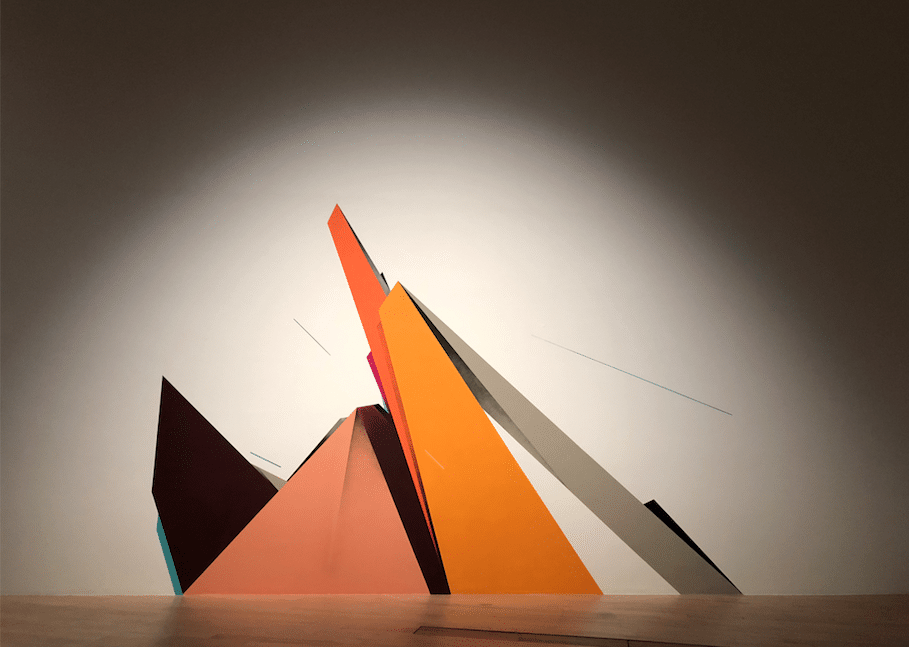

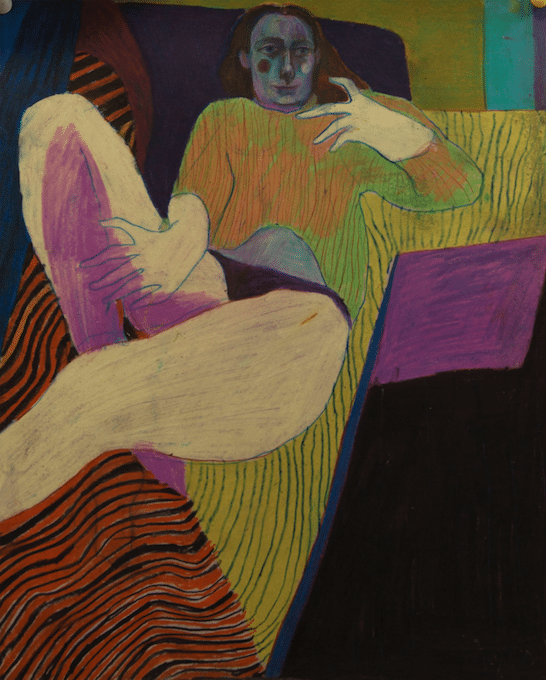

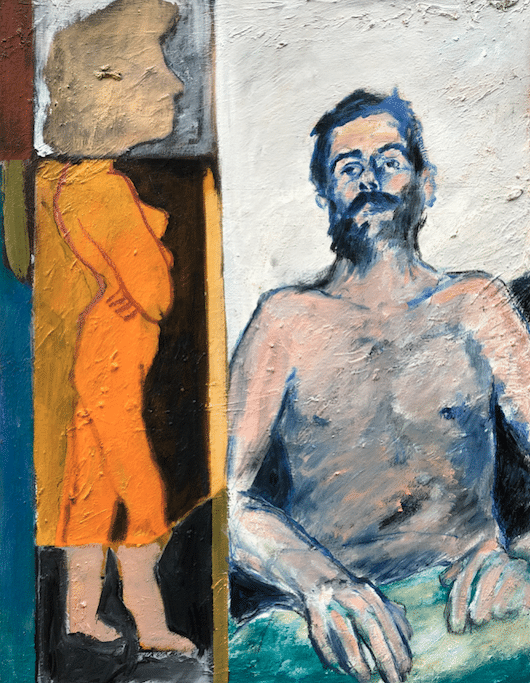

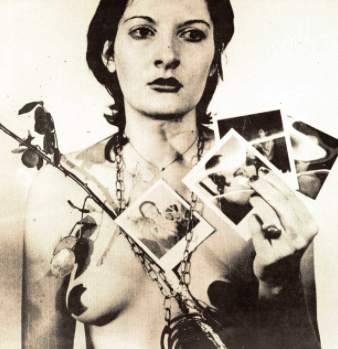

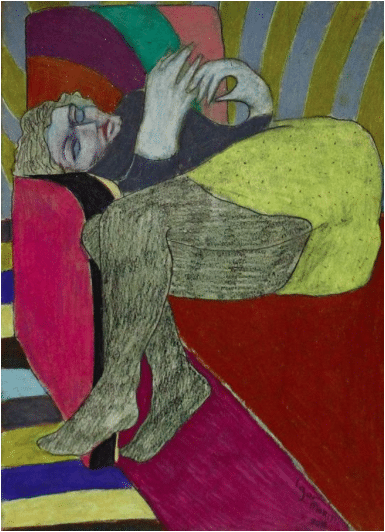

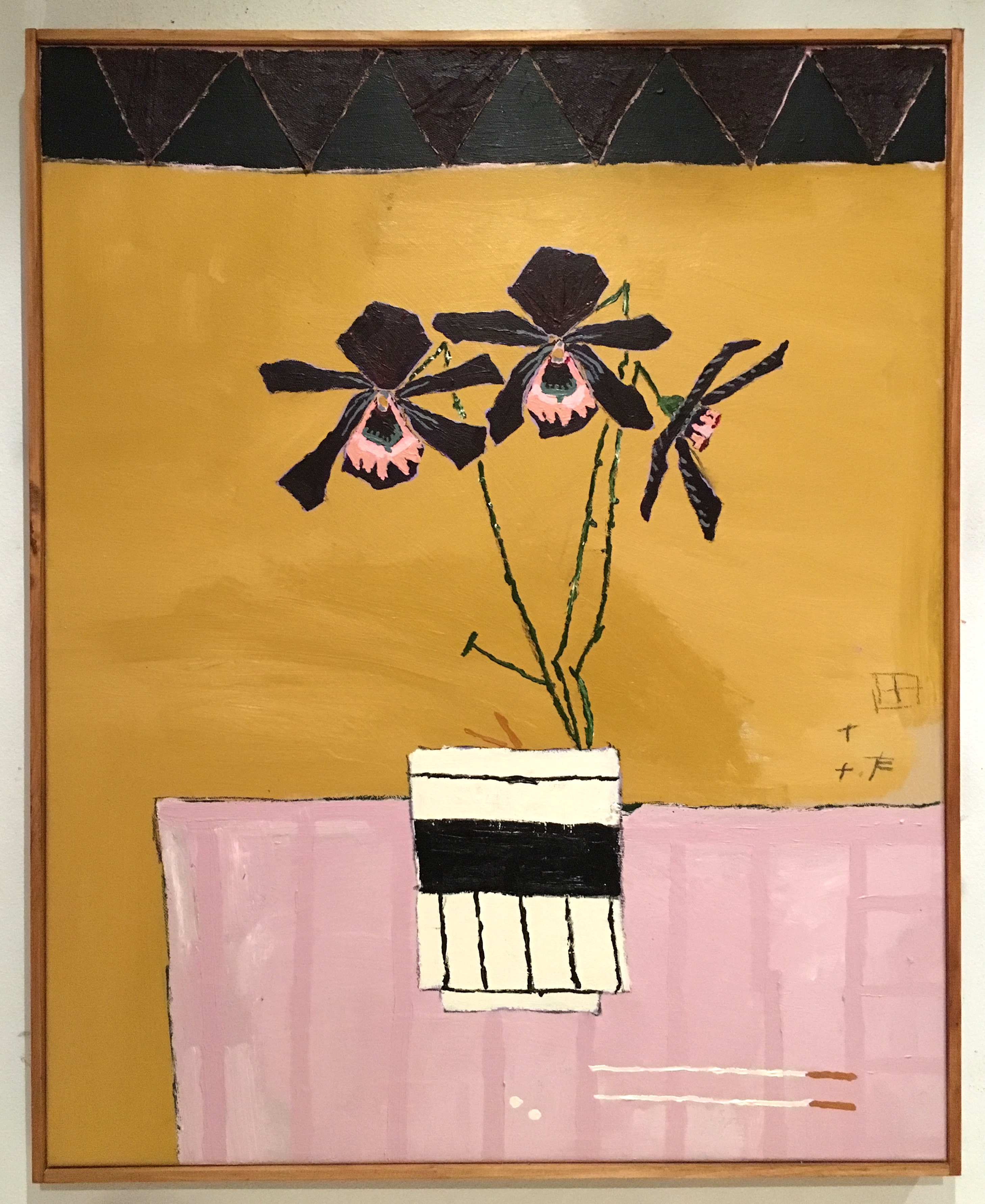

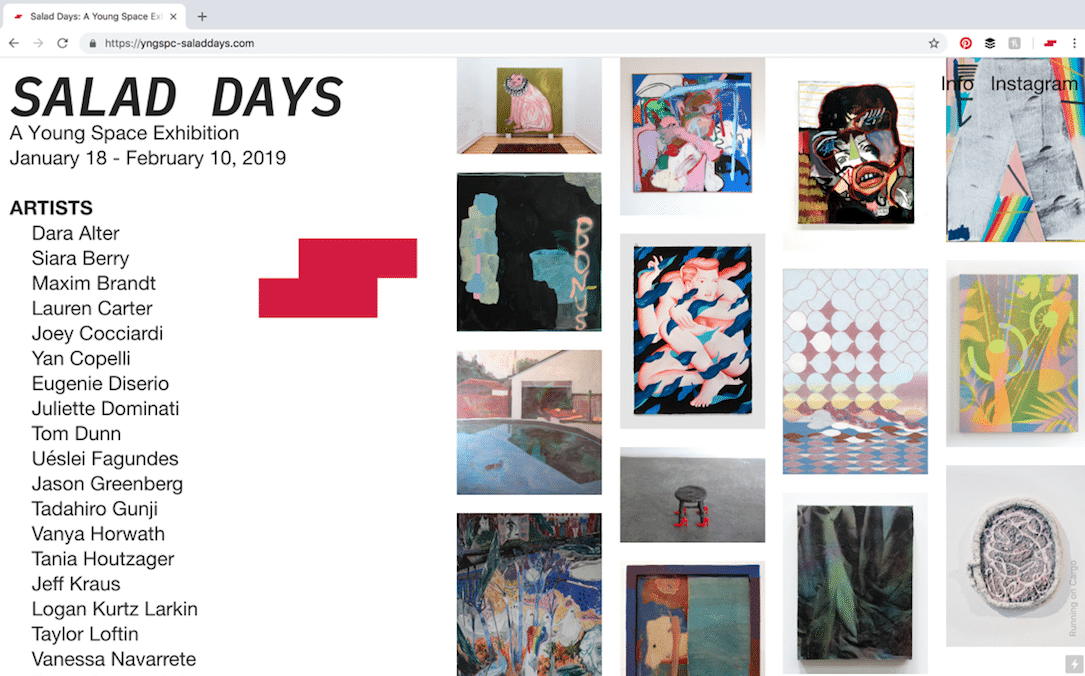

Salad Days – an online exhibition with Young Space

(This column came from a late-night post on Facebook, which generated a discussion that I was thinking about for days after. When social media is genuinely social, it can be incredibly rewarding. This column is essentially that Facebook post, edited for clarity, with some of the thoughts from comments woven in.)

There’s a misconception (which I subscribed to for a long time) that everyone in the art world is rich. Like, stinking, rotten rich. They have this beautiful white cube space; they take collectors out to dinner; they’re jet-setting from art fair to art fair; they’re dealing in fine art, a luxury item, for crying out loud. “They” feels totally disparate from “me,” the indie creative person, plugging along, disconnected from the glamour I associate with that lifestyle. It’s a lot more complex and stratified than that now, and the internet can be both blamed and lauded for its ability to simultaneously mask and manufacture ideas about that lifestyle.

It’s easy, as an independent creative, on principle, to assume that the big guys are always out to get the little guys. Does anyone else assume that everyone else on Instagram is rich? Or has the luxury to make art 24/7? I do too, and then I have to remember that it’s an aspirational platform, and much of this is fabrication, or an omission of the details that make life livable – working 60 hours per week, taking care of a house, getting the kids to school on time, and soo on. It’s easy to mistrust what looks a lot like big money, when money is something you generally scrape by for. The internet has already changed that “them vs. me” mentality, and continues to do so, and I, for one, am doing something within the art world that would not be possible without the internet. So why am I still so confounded by it?

I alternately describe myself as a curator, a presenter, an influencer, an organizer, or a producer, or simply a collaborator, depending on what I’m working on that minute. I also acknowledge that I’m working within a globalized contemporary art world – somewhere in between artists’ studios and commercial galleries’ back rooms – and that’s a wide net to cast, and the depths are blurry. Also, the vast majority of everything I do is online, a playing field that has been leveled by social media platforms to allow for more ways to showcase and access art, while at the same time raising questions about how it’s homogenizing the field itself.

I currently live in a blue-collar city in Northern Wisconsin, where I grew up and where it is exceptionally affordable. It’s a place where, however, the art scene we associate with New York City, London, or Hong Kong, does not reach one spindly tendril. I justify to myself that I’m here because there’s an ironic cachet to rurality in contemporary art, and it’s a little bit weird, but the truth is that it’s out of sheer necessity. There is simply no way I would be able to focus as much time and energy on the creative route I’ve found myself on, if I was a rent slave in New York. Every day, though, I wish I could be there. So, I use the internet to keep a finger on the pulse, establish connections, and work on projects. I’m always remote. And I am connected to countless others online who operate in a similar way.

The internet, which billions of us now use, is at the center of my (hopefully not too navel-gazey) fascination with the directions that the art world moves, how opportunities are generated, and how attitudes toward various art world geographies and players continue to shift. Its role in the arts is paradoxical in that it is essential across the board for myriad reasons, from advertising to networking, however it can be seen as a necessity or an alternative. Where that line is drawn depends entirely on who’s using it, and who their audience is.

There are advisors, consultants, developers, designers, curators, artist-curators, brokers, nomadic spaces, publishers, online auctions, Instagram galleries, virtual spaces, etc. The ways that artists can reach audiences these days is AMAZING. But we’re still not comfortable with the fast pace at which the Internet, and the way we look at art, is changing how we make, learn about, and purchase artwork. In the digital age, we try our best to keep up with how fast the art world moves, at the same time knowing that the digital sphere is the epicenter of innovation today. The art world is no exception.

From a more philosophical point of view, assuming that there is or should ever be one way of looking, finding, experiencing, interacting with, making, or sharing artwork = absolutely ludicrous. Because I was raised by artists, resisted academia despite the pressure to pursue it, was influenced by artist-led culture, and have always been driven to DO and MAKE as a way of being, I’m hard-wired to see alternatives to everything. Not that the way I want to do it is better–it might fail horribly–but if it hasn’t really been done this way before, or if I have a certain set of tools in my toolbox that I didn’t before, why shouldn’t an alternative at least be attempted?

The Internet has revved up to hyper-speed the rate at which we experience, view, participate in, and connect with art and art people. Without it, my project, a nomadic online-offline curatorial contemporary platform called Young Space, would not exist. I’m extremely interested in how fast things move and what sort of information we as creatives share online. How can we use this as a vehicle? How does it help? How does it hinder? What are the limitations, and what are the open horizons?

I’ve been doing this experimental series of online exhibitions, the most recent called Salad Days, which has had a great response. However, I admit I feel weird about these. I feel weird because they’re not “real.” But then I mentally slap myself and think, DUH, YES, THEY ARE REAL. They are very real. And I want to do more of them.

Why do I feel like these are not real? Maybe there’s a disconnect between the “analog” artwork and the “virtual” vessel. This may feel difficult to reconcile, even if all of the other pieces of the puzzle add up to a very traditional way of presenting a show… it’s simply that the exhibition space is a website. Is that stilla scary idea? The question is perhaps not so much is it a scary idea, but to whom.Because, in fact, almost all of the complaints I receive are from artists, and I would argue it’s because there is still a perception that the internet is simply “easier.” I’m arguing that it’s not; the work and time we invest just looks different.

These online shows have been more popular and just as well-received as the physical shows I’ve curated (so far), so I’m really intrigued as to why, when I do an online show, I receive much more flack for it than when I do a physical one. Full disclosure, it usually has to do with either a fee required to apply, or commission taken from sales. These are sore spots for artists because there’s already so much expense to just make the work, let alone the time invested. (I think it’s a mistake to proclaim that pay-to-play is, across the board, horrible. YES, sometimes they are really lame. But if one does their research, it’s not difficult to find out if something is legit, and if that person is really working in your best interest. That is an essay for another time.)

There seems to be a bizarrely fine line between the idea of “supporting” artists and “exploiting” them. Money is still the core of this, which is unfortunate and ironic, as artists are educated in making art for art’s sake, but realistically they are thrust into an art world that values the appearance of that, but the bottom line is still about sales. This points to a big debate within art schools about whether to teach artists business practices. Because the art world artists strive to get into is about money. Art for art’s sake? Sure. But you still need to eat.

Online exhibitions are not new. I’m fascinated that they are such a tender spot. For example, Artsy offers a resource called ‘The Gallery’s Guide to Online Exclusive Shows.’As I see it, online shows are more accessible than a physical space. More people can see them, in any part of the world, at any time of day. It’s less expensive, as there’s no need to rent space, or pay for packing or shipping. That money can be spent on increased advertising, web fees, saves artists the trouble shipping work unless it sells, and the artists still have documentation of a professionally curated exhibition. The work does sell sometimes, but sometimes it doesn’t, of course.

I, for one, don’t think in dollars and cents about online shows. Young Space is not really a commercial venture – it’s a curatorial platform. It’s a “project.” The value comes from a different direction: I’m attempting to position myself as a facilitator for these artists, as opposed to acting as a dealer. I can’t even count how many artists from my Instagram or exhibitions have been selected for exhibitions or projects, not to mention galleries’ rosters! (Do I get a cent from any of that? No.)

Perhaps trouble arises because of a problem that is as old as the internet itself: Can I trust that you are you who say you are, and that you will do what you say you will do? How is this different than any other Instagram account? Who do you know? What are your credentials? (My answer to that is always DO YOUR RESEARCH. Ask. Don’t assume that everyone’s out there to get you.) Pro tip: Artists, don’t be accusatory, arrogant, or assume you know everything right out of the gate. If you do, you can bet I’m never going to want to work with you, or recommend you to anyone, period. I would never presume to know how someone else’s work was made, having never tried myself.

Salad Days – an online exhibition with Young Space

Recently, smaller galleries are shuttering their doors, decentralizing from urban cultural centers, or pursuing online platforms. Gallerists that once maintained brick and mortar locations are now dealing artwork without the real estate overhead. They’re in a double-bind, because they have to keep up appearances, and yes, keep with tradition (the comfort of the brick and mortar, the philosophical dilemma of getting rid of a physical space and still being able to call oneself a gallerist), even when they are struggling. If they admit they’re not doing well, they look like they can’t hold it together, rather than the opposite being the case: rising rents are not only forcing artists out, but galleries too. If they pretend they’re doing just fine when they’re actually freaking the F out, they’re fighting a losing battle too, because they’ll eventually not be able to sustain at the same pace, and they’ll fold anyway.

Advertising and fair fees are immense, the pressure to do them is intense, and competition can be cutthroat. There are the motherships – Gagosian, Saatchi, PACE and the like. There are some great mid-tier galleries, excellent smaller galleries, and some very exciting startups. Great galleries are often side hustles. I’m not saying there aren’t some seriously putridly rich people out there; many of them are. But many are just doing OK.

It’s worth remembering that artists have historically been kept separate from the art world until they are “welcomed in” by a gatekeeper, whether it’s a gallerist or a collector or simply someone who knows someone. In a sense, even my project Young Space is like a lower-tier gate – one that aims to offer early career and emerging artists the chance to have their work showcased to an audience comprised of gallerists, curators, collectors, and other artists. The competition is fierce, the animosity spreads like moss… it takes a lot to keep your chin up, let alone find emotional or mental room for optimism when you feel like you’re getting overlooked again and again. It’s not that you don’t have something of value to offer; it may be that the time is just not right yet.

Regardless, there’s a system in place and there are rules. Rules that supposedly can be broken–but can they? There are things that are simply “not done,” like the classic no-no of walking into a gallery with your portfolio hoping they’ll be inspired by your courage and place you on their roster. But of course, feel free to innovate or approach those boundaries all you like… at your peril. There is so much code-switching in the art world, it boggles the mind. The internet, though, is a place where there is power to influence and to be seen, as the connectivity we can achieve now, via social media especially, was unheard of a decade ago.

No, an online show will never be the same as viewing work in person. Never. But I find the resistance to–and cynicism toward–virtual modes of sharing artwork a little awkward at this point. This is a whole new realm of connectivity, and as creatives this is what we do. This is the game! Try weird shit! For a while I was irritated and took criticism about these things personally (Young Space is a solo project after all, it’s sometimes hard to disengage). But I’m realizing that this nerve is perhaps exactly the reason it’s worth exploring.

For more guest articles, see Charley Peters’ interview with Remi Rough